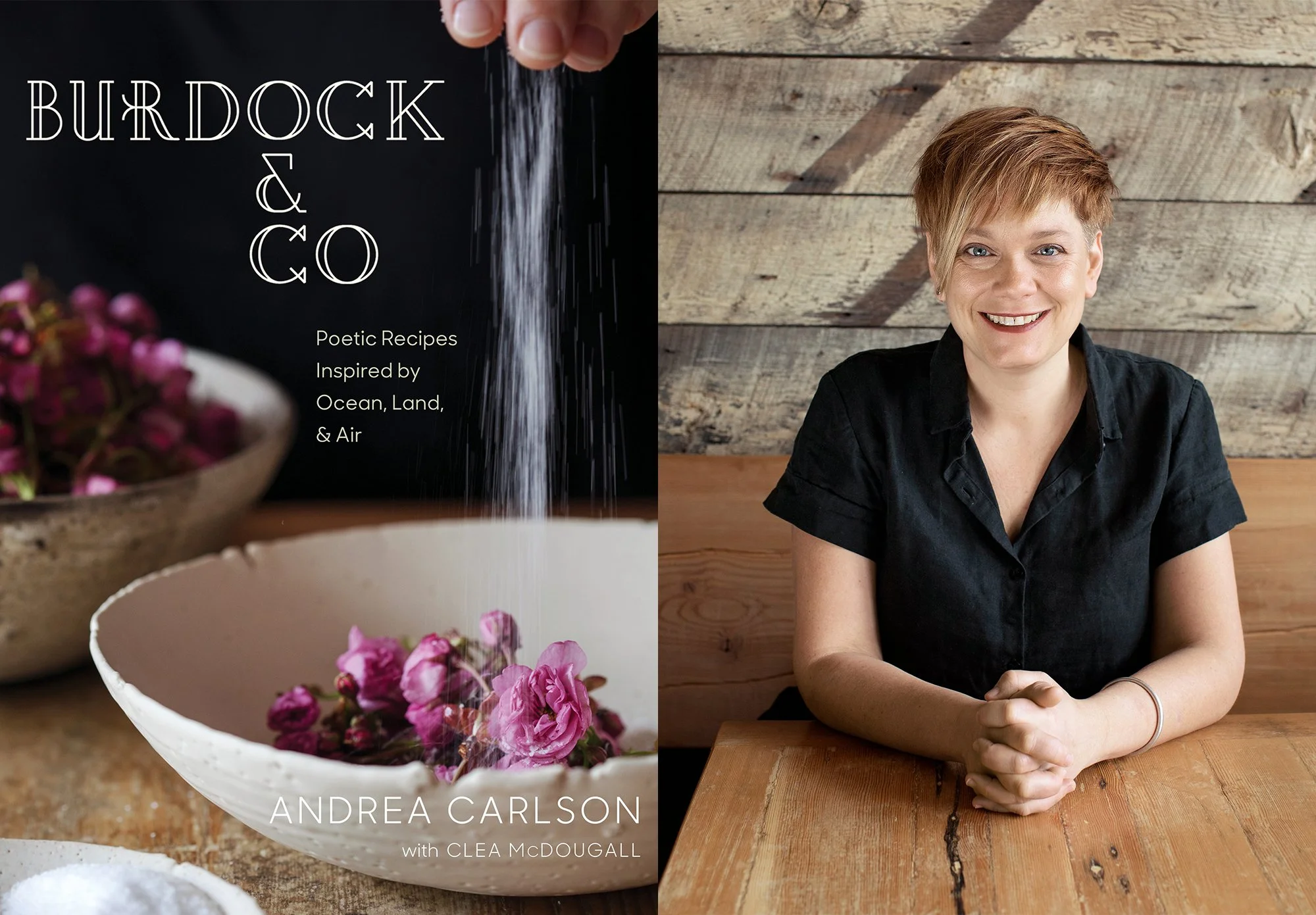

West Coast Darling Burdock & Co. is Getting its Own Cookbook

Chef Andrea Carlson's harvest table.

The humble turnip: it’s usually not the first thing that springs to mind when people are asked to name their favourite vegetable. Yet it was one bite of a fresh turnip, newly harvested from the fields of East Sooke on Vancouver Island, that turned chef Andrea Carlson’s perspective on farm ingredients upside down. She was working at Sooke Harbour House with Sinclair Philip—godfather of the seasonal and ethical locavore movement—and the kitchen crew was challenged to create a new menu each day. “It was a pivotal moment of learning,” says Carlson. “If one of the most maligned, underappreciated root vegetables could taste so incredible, what else was there in store within the realm of fresh ingredients from the field?” It was an epiphany that crystallized her culinary purpose and set a lofty precedent for her future endeavours.

Carlson’s early experiences with food were inauspicious. Frozen dinners and packages of cookies and chips were her staples as a latchkey kid growing up in Toronto; family meals were far from memorable, and her mother would always say she had learned to cook as a survival tactic. But a flicker of interest sparked for Carlson at age 13 when she picked up Craig Claiborne’s New York Times Cookbook. It led her to explore classic recipes by Julia Child and Pierre Franey, and she began making dishes like chicken parmigiana when people came over for dinner. “At the time, I didn’t realize how much those first forays into cooking really meant to me,” she reflects. “But I found myself gravitating toward culinary school because I loved the tactile aspect of cooking and how actively it engaged all my senses.”

After her studies at Dubrulle Culinary Arts (now part of LaSalle College Vancouver), Carlson did a stint at Star Anise, Adam Busby’s celebrated French restaurant in Vancouver, before opening Sunflour Bakery on Savary Island in 1997 with her life partner, Kevin Bismanis. They ran it together for eight months before he started architecture school. “[The island is] a little off-the-grid paradise,” she says. “Every morning, we’d walk barefoot [through the forest] to a nearby spring and collect water for the day’s bread. To this day, it’s still one of my most treasured food memories.” This pared-down way of living reinforced her connection to the environment, and her involvement in sustainably minded organizations such as Friends of Clayoquot Sound and the Sierra Club dovetailed neatly with the culinary path she was about to follow.

In 1998, Carlson joined the kitchen brigade of Robert Clark’s C Restaurant as sous-chef. Clark’s impassioned philosophical approach to cooking and commitment to helping launch the Ocean Wise sustainable seafood program resonated deeply with Carlson. “C was really the first restaurant in Vancouver that actively advocated for a conscious approach to our food systems and paved the way for moving in that direction.” she says. “It’s what started me on the path of sustainability.”

At this point in her career, Carlson was looking to stretch her wings. She had known about Sinclair Philip for years and was drawn to his reputation for breaking new ground in terms of a chef’s approach to local eating. She joined him at Sooke Harbour House, where his three-acre garden was a veritable paradise of rare herbs and edible blossoms, including flavours and ingredients she’d never worked with before. “My palate grew by leaps and bounds. Sinclair taught me so much about the beauty of subtlety.” His methods for sourcing regional ingredients—diving for sea urchin and harvesting seaweed—were virtually unheard of at the time and were considered quite exotic. “One of his strongest influences on me was in menu writing. Sinclair was very precise about language. He’d never say parfait or chawanmushi. Instead, he’d detail a very, very specific expression of what the dish was, without appropriating some sort of cultural dish.” “Seaweed” wasn’t referenced; rather, it was one of the four varieties of kelp that had been harvested. And he eschewed the more colloquial term “spot prawn” in favour of the accurate term, “spotted shrimp”.